| History of Japanese Manga Comics |

|

The Beginning of Manga

As to the origins of Manga, there are various theories. One argument is that the origin of manga comes from the basic human desire of wanting to express and record - hence referring to the origins of manga as being that as fundamental as scribbles and doddles. The 20thC great master of manga, Osamu Tezuka is recorded to have stated that 'manga begins from scribbles'. If one goes by this theory, we can argue that the origins of manga can stem as far back as the Stone Age scribbles on the cave walls. Specifically relating to examples cited in Japan, a few theories point to the scribble on the back of the ceiling board of Horyuji Temple (the oldest wooden structure in the world dating from 607) as being the first example of scribbling - in other words, the grandfather of manga in Japan. The doodling most likely done by one of the carpenters during the construction, is that of a human face.

|

Fukutomi Soushi 14th C

|

Other theorists point to scroll paintings as being the origins of manga. Although not separated by the borders that exist in modern day manga, there is a stylistic similarity, but more importantly, it serves the function of telling a story as the viewer casts their eye through the scroll - unlike being just a picture. One example of this is the scroll Fukutomi Soushi, from the 14th C that tells of the story of a character whose greed and gullibility turned him to thinking by means of his skills of flatulence, he could gain success and wealth through performing - only to end up in shame. This scroll also stands also as one of the first examples of the beginnings of speech bubbles, as the speech of the characters are inscribed adjacent to the characters depicted in the scroll painting.

|

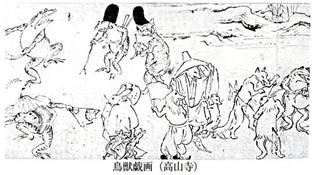

Other arguments state that the origins of manga must be those that contain an element of humour, and many point to Choju Giga (Illustration of Frolicking Animals) attributed to the monk Kakuyu (1053-1140) honorary title Toba Sojo, as being the first origins of manga. Particularly during the early 18th C named after the monk, Toba-e became popular. This was an art form that involved humour and depiction of comic situations. Examples of Toba-e include Tobae-sangokushi amongst others.

|

Choju Giga(Kozan Temple) 12th C - 13th C

|

Development of Manga

|

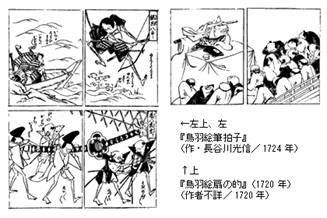

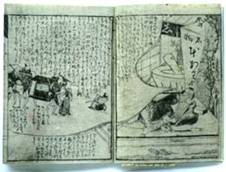

Tobae Fudebyoshi (1724) / Tobae Ogi no Mato (1720)

|

The wide distribution of the primitive versions of manga, took place from the early 18th C with the development of woodblock printing enabling multiple production. The first book form of such work was Toba-e books that were distributed in Osaka.

Left : Tobae Fudebyoshi (1724).

Artist: Mitsunobu Hasegawa.

Right : Tobae Ogi no Mato (1720).

| |

Later in the early 18th C, giga (caricature) images became commercially available to the public, and by the 19th C, major woodblock print artists began producing prints with the influence of giga images. Such examples include the numerous giga prints produced by Kuniyoshi (1797-1861).

|

|

One reason for the widespread popularity for the giga prints were partly owed to the strict feudal system of 19thC Japan that banned any production of Japanese prints that contained any political elements. Some of the prints produced in the giga style, without doubt had satirical elements - however, it was something that due to its comical style, was regarded not as an attack but as a form of amusement and entertainment, and therefore were not penalised. However, even satirical prints in giga form, were never strong political statements as the artist invariably faced punishment under the laws of the shogunate.

Amongst the kibyoshi (yellow back satirical books for adults) tale books that flourished in Japan between 1775 to around 1806, there is a publication, kinkinsensei eiganoyume (1775), often sited as one of the first examples of the use similar to speech bubbles, where a man is illustrated having a dream.

|

Amongst these various examples of 19thC illustrations, the prime example and perhaps the best known and regarded by the majority as being the ancestor of manga, is that produced by the grand master of woodblock prints Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) the 15 volume series of books Hokusai manga. It had an impact as far as Europe. Images in the volumes include illustration of lines to depict air breathing though nostrils. ie the earliest examples of what is referred to as manpu in Japanese - symbolic illustrations to depict expressions, feelings, or even sound, that is particular to comic illustrations (a method of illustration that is removed from realism and not seen in art in the traditional sense). However, since the volumes of Hokusai manga were published by Hokusai as an artistic manual for his students, to say this was the manga of the 19th C would be inaccurate. The title of these volumes include the word, manga, however the notion and meaning of the word was totally different to the meaning of the world understood by modern people. Click here for description of the word and characters used for the word "manga". However, without doubt, judging from the size of the publication and the style of illustration, one can draw a parallel between Hokusai manga and the manga that exists today.

Kinkinsensei Eiga no Yume (1775)

|

Influence from the West

|

Japan Punch (cover) by Charles Wirgman (1862-1887)

|

There is an influence of the West that makes an impact in the progression of Japanese manga to what it is today. During 1862-1887 in the first Japanese magazine published in English was "Japan Punch" published by Charles Wirgman, a correspondent for the "Illustrated London News". With great observation, he entertained readers with comic satirical depiction of the rich, the politician, the missionary, the sailor and the merchants of the local area. The main character, Mr Punch, was conjured up by Wirgman as perhaps an alter ego of himself in the publication, which enabled an insight into 19th C Japan with its modernization and historical events illustrated through the comical and humorous illustration through the observing eye of a journalist.

There existed in the same period a comic publication named "Punch" in the UK, and though it is not certain as to whether it was from "Punch" or from "Japan Punch", a new name was coined in Japan - ponchi-e (Punch picture) - which referred to satirical or fable publications. Influenced by such illustrations, the artists Kyosai Kawanabe and Robun Kanagaki produced e-Shinbun-nihon-chi Magazine. Following this in 1877, regarded as the leading comic magazine Marumaru-chinbun was published.

|

The inset shows an image from a series 'Mr. Briggs' that appeared as a series in the "Punch" magazine. Many episodes were in fact two-panel cartoons, of which Mr. Briggs was one of the earliest serialised comics to be introduced in magazines. The Japan Punch by Wirgman, no doubt was influenced by this, and although word speech concepts clearly already existed in Japanese art and books from earlier periods, the heavy use of speech bubbles seems to have come at this point.

By this time, with the feudal system overturned and the strict censorship laws of the shogunate no longer being in existence, the new government was far more relaxed in regards to such satirical images of current affairs. The influence of these western artists perhaps not so much the style, but certainly made an impact in making artists realise the popularity and potential commercial success of producing satirical and comic images that directly related to the people.

Manga - Japanese comics

Similar to photography and cinematography, comic books were an art form that was not known in Japan as such before the 19th century. Although ukiyo-e represented a mature visual form, indisputably on an advanced graphical level, and regardless the fact that it was closely connected to literature, folklore and mythology and often represented famous historical scenes, the idea of a narrative told by a sequel of images followed by an appropriate text was invented in the West.

The main difference between the first Western comic strips that started appearing in newspapers around 1900 and the ever-popular 'pictures of the floating world' from the Meiji period Edo was that the later lacked any political massage or intellectual criticism, which would be considered rude and offensive in Japan of the time.

The form, however, rapidly developed in an atmosphere of intellectual creativity of the '20s and '30s and one of the first manga magazines to be published in Japan - Shonen Club recorded sales of 900.000 copies as early as 1931. After the WWII, whereas American comics got restricted by the new censorship laws, manga exploded into the most productive cultural industry of Japan, marking the aesthetics and visual concepts of the new generations.

What distinguished Japanese comic books from the rest of the world was actually the rich heritage of the traditional painting and craftsmanship, as suggested by the very title of the form. Centuries of sophisticated and complex print-making tradition manifested in the modern-day comic books by the selection of subjects as well as by the specific and particular use of perspective.

Thereupon, comics in Japan were always meant for everyone and dealt equally with the topics from everyday life same as with fantastic stories, while they were offering complete visual, almost cinematographic experience, with the text being used more as means of providing special effects in the background. The reason is that Japanese artists sometimes use more than 20 pages per single scene, thus visually presenting the entire event, which again can be put into a single sentence. Therefore, comics are not merely 'read' but more 'seen', an experience which is close to the understanding of Japanese language itself, which can be a reason for the initial development of a specific artistic preferences and therefore style in the first place.

Keicichi Suyama, a manga researcher, states in the "Hisory of manga Journal : World Edition 1972" translates the word manga as Cartoon, or caricature.

|

|

|

|

|